Influenza, or the “flu,” is the result of a viral infection that affects the respiratory system. It is caused by viruses in the family Orthomyxoviridae, which have single-stranded RNA genomes. Flu viruses can cause fever, aches, muscle fatigue, congestion, coughing, and sore throat. The flu is usually significantly worse than the common cold and often comes on very quickly. Most people can fight off the infection on their own with no residual side effects. However, there is no “cure,” and it can be fatal, especially for those who are more vulnerable: the immunocompromised, young children, the elderly, and people with chronic diseases, who are more susceptible to secondary illnesses like pneumonia. Despite the fact that most infected people do not die from the flu, the high number of cases alone results in a significant number of deaths. According to the CDC, influenza has caused 9,000,000 – 45,000,000 illnesses and 12,000 – 61,000 deaths annually in the U.S. since 2010 (these are not range estimates, but the highest and lowest estimates from individual years, the lowest being from the 2011-12 season, and the highest from 2017-18).

There is a vaccine for the flu, but it changes every year due to the antigenic drift that occurs in flu viruses. The RNA genomes of these viruses and their use of RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RDRPs) to replicate their genomes leads to a high mutation rate. RDRPs are very error-prone and do not have the proofreading abilities of DNA polymerases. This regular antigenic drift means that we can’t just vaccinate a couple times against flu and be done with it, like we can with other viruses such as chickenpox.

Twice a year, influenza experts meet at the World Health Organization (WHO) to predict the dominant strains of the next year using all of the data collected in the past year by health care providers. Strain selection for the Northern Hemisphere occurs in late February, and strain selection for the Southern Hemisphere occurs in late September (the winter season in the Southern Hemisphere is during the Northern summer months). After selection, it then takes about six to nine months to develop and produce the vaccine for the upcoming flu season. The flu vaccine is designed to protect against the 3-4 most dominant strains of flu virus that were predicted earlier in the year.

The flu shot is not 100% effective. In years when the vaccine is well matched to the viruses present during flu season, it reduces flu illness by between 40% to 60% among the overall population. It can be even lower in years when the vaccine is not well matched, such as in 2014-2015, when the U.S. Flu Vaccine Effectiveness (VE) Network estimated the VE to be only 19%. However, getting the flu shot is still always a good idea. Studies have shown that even when vaccinated people get the flu, they are more likely to have less severe illness — which means mitigated symptoms, reduced hospitalization, and fewer deaths.

People should not avoid getting flu shots for reasons like: “Well I got the flu shot before and it gave me the flu.” Flu vaccines cannot give people the flu, because they only contain inactive (killed) viruses or a protein-coding gene that will stimulate an immune response without the infection. If someone gets flu-like symptoms after vaccination, it is likely because of a similar viral infection (read: common cold). It could also be due to a strain of the flu that the vaccine does not match well, an infection with the flu that occurred before the vaccination could take effect, or the vaccine did not work (for reasons other than a poor match). It would not be because the vaccine itself gave someone the flu.

In addition to getting the flu shot each year, people can also reduce the spread of the flu by washing their hands regularly, containing coughs and sneezes, avoiding sick people, not touching their eyes, mouth, and nose, and reducing time spent in crowded areas. There are also antiviral treatments for the flu, but they can only reduce symptoms and are most effective when given early in the infection.

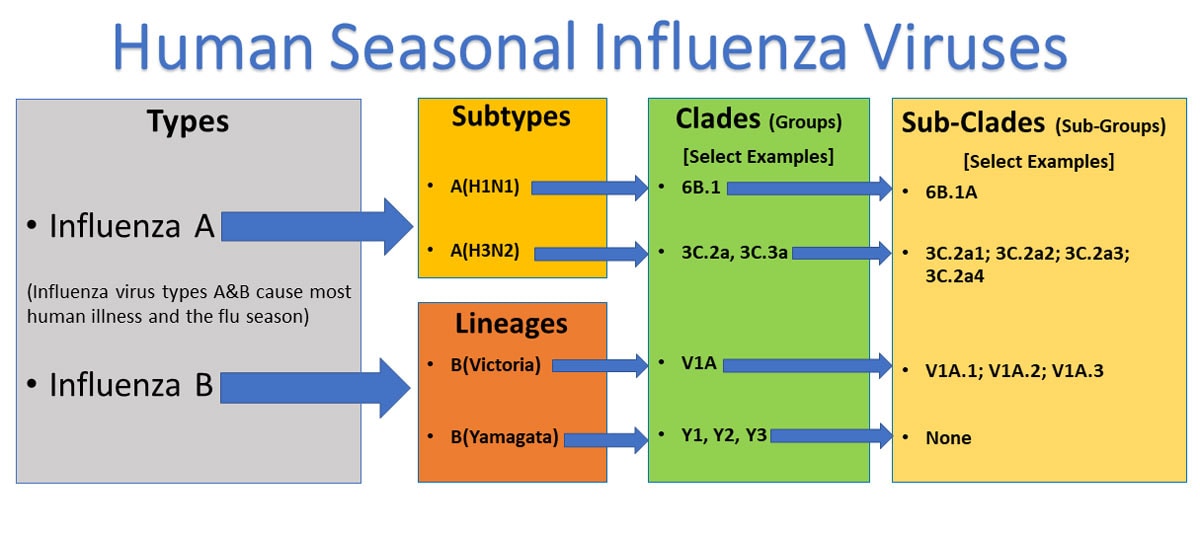

The 2019-2020 Northern Hemisphere version of the flu vaccine includes (Influenza) A(H1N1) and A(H3N2) vaccine components, and (Influenza) B/Victoria and B/Yamagata vaccine components. The four strains used were predicted to be the most dominant in spring 2019. In September 2019, the strain selections were being made for the Southern Hemisphere’s 2020 flu season, and it was concluded that “the H3N2 and B/Victoria viruses needed to be updated because the ones used in the Northern Hemisphere vaccine didn’t match the strains of those viruses that are now dominant.”

The CDC has not yet calculated the vaccine effectiveness (VE) for this year, because it is still too early to give an accurate number. However, the CDC has performed antigenic characterization (analysis of the viral antigens, which are the surface molecules needed for the immune system to recognize and respond to the infection) of 241 influenza viruses collected from health laboratories in the U.S. from September 29, 2019 to February 1, 2020. This is used to compare the most recent influenza strains to the reference strains used to develop the flu vaccines, and the results support the concerns stated back in September. The A(H1N1) and B/Yamagata reference viruses (vaccine components) were a match (antigenically similar) to 100% of the viruses that were characterized into their respective subtype/lineage. The A(H3N2) component only matched 43.5% of the collected A(H3N2) viruses, and the B/Victoria component only matched 60.2% of the collected B/Victoria viruses.

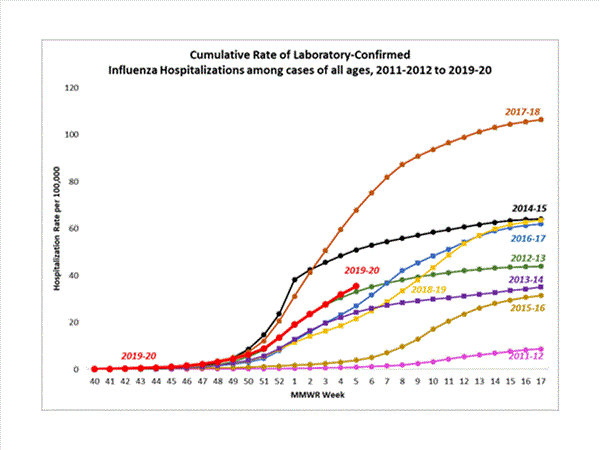

Despite the mismatch between some of the 2019-20 vaccine components and the flu virus population, the vaccine has been fairly effective, and there has not been an abnormal increase in illness, hospitalization, or death rates this year. The CDC estimates that from October 1, 2019 to February 1, 2019, there have been about 22,000,000 – 31,000,000 illnesses and 12,000 – 30,000 deaths in the U.S. due to the flu. So far, this is on par with the past 10 years (low of 9,000,000 illnesses and 12,000 deaths in 2011-2012, and high of 45,000,000 illnesses and 61,000 deaths in 2017-2018). The rate of influenza-associated hospitalizations is also similar to previous years with a current cumulative rate of 35.5 per 100,000.

What is interesting about the flu is that everyone generally knows what it is, yet the vaccination rate for the annual flu shot is not impressively high. According to the Census Bureau, there are approximately 330,000,000 people in the U.S. Yet only 173,000,000 flu vaccines have been administered this flu season. Even assuming that each vaccine correlates with one person, that is still only about half of the population. Maybe there is not as much awareness about the potential complications of contracting the flu. Or people know the risks, but take the “it won’t happen to me” approach — no different than those who drink and drive, smoke cigarettes, or allow themselves to gain an extra hundred pounds. Maybe people aren’t convinced by the personal cost-benefit analysis: “I could inconvenience myself (ugh) to do something I don’t like (see a doctor, get a needle stuck in my arm) to maybe get a 50% improvement in my odds of not getting sick. Eh, pass.” Still others don’t “believe” in vaccines. The flu vaccine is too widely available for inaccessibility or inconvenience to be a legitimate widespread excuse. Flu-related deaths are a part of the status quo, just like car accident fatalities. The media certainly doesn’t talk much about it. Unless there is a wild new viral strain (such as the H1N1 pandemic of 2009), few are bothered by the fact that tens of thousands of people die each year in the U.S. due to the flu (and far more worldwide). And much like fatalities due to car accidents, many of these deaths are preventable.