My mom is a ER doctor, and she is old enough to have practiced during the HIV/AIDs epidemic of the 1980s. Since I was not alive at the time, it is impossible for me to understand what it was like, and I can only imagine how confusing and scary it would be to see this new disease suddenly causing large groups of people to die after a period of painful physical degeneration, with no understanding of why or how it was being spread. The effects of the epidemic were only compounded by the politics of the disease slowing research and treatment. My mom has talked about how not all medical staff were willing to see (be in close proximity with) AIDs patients, especially before they figured out how it spread. My mom also had a needlestick injury from a confirmed case, and she was treated with AZT for some time (Never again!, she says), which was a miserable experience all around. Although now we know that the risk of getting HIV through needle sticks in a hospital setting is relatively low, this was not known at the time.

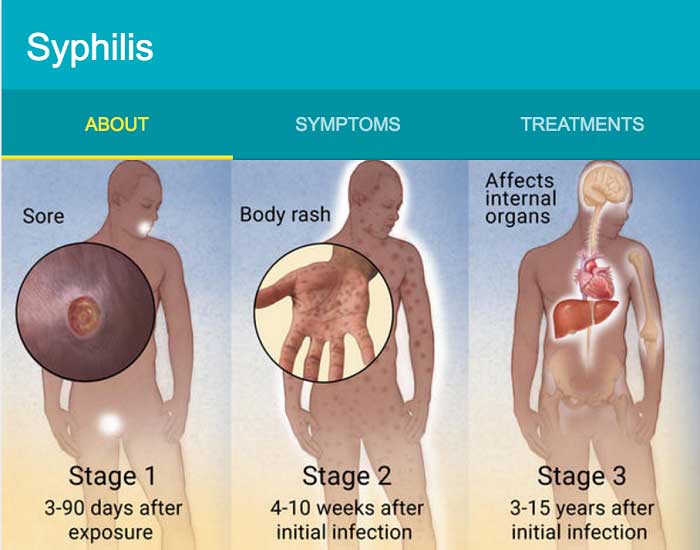

HIV stands for Human Immunodeficiency Virus, and it is responsible for the disease AIDS, or Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome. HIV can be treated much better today — it is no longer a death sentence — but it is still a “lifetime commitment.” It is one STD that cannot be completely cured, or removed, through treatment. HIV attacks the body’s immune system, specifically helper T cells, and over time it compromises the immune system to the point where it cannot fight off infections. People who die from AIDS don’t die from the disease itself so much as an opportunistic infection that can’t be fought by the weakened immune system. Today, HIV can be controlled through a treatment called antiretroviral therapy, or ART. When taken correctly, it can reduce their viral load to the point where they never reach the end-stage disease we call AIDS, and people can live with HIV for decades. However, ART was not introduced until the mid-1990s, and before that, people could die within a few years of infection. HIV is spread primarily through unprotected sex, although it can also be spread through needle sharing, blood transfusions, and from mother to child. HIV is NOT spread through saliva, sweat, tears, food sharing, toilets, air, water, or casual contact (e.g. hugging or shaking hands).

HIV was first brought to the attention of the United States when there were cases of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP) in young, healthy gay men in Los Angeles in 1981. There were also reports of gay men with Kaposi’s Sarcoma, a particularly aggressive cancer, in New York. Both diseases are associated with immunocompromised people, but these men had all been previously healthy. As more cases came out, the disease was first dubbed “gay-related immune deficiency” (GRID), although the name was later changed to AIDS in late 1982. France and the United States raced to find the cause of the disease, and France found the virus first, calling it Lymphadenopathy-Associated Virus (LAV) in 1983. In 1987, the first antiretroviral drug, zidovudine (AZT), was approved by the FDA as treatment for HIV. Although AZT worked, it had many side effects, and HIV inevitably developed resistance. It wasn’t until the mid-1990s that ART was developed, a much more effective long-term treatment for AIDS that is still used today. By 2000, over 14 million people had died from AIDS from the beginning of the epidemic.